My Path to Becoming a Psychologist

I majored in Psychology as an undergraduate only because those courses and instructors most caught my interest—the future was not yet situated in my priorities in those growing years. I was especially drawn to courses in personality and attitude theory. I only had a vague notion of what a therapist actually did, and certainly no notion that I would become one. Honestly, I spent more time on a racquetball court than I did in class, not exactly the poster child for well-planned pre-professional training. My kill shot was undoubtably better than my research acumen. Upon graduation, I cogitated…what next? I finally came to, after 16 years of my life being a student it was time to get a different experience of the world. Where my journey really began was when I joined the Peace Corps…

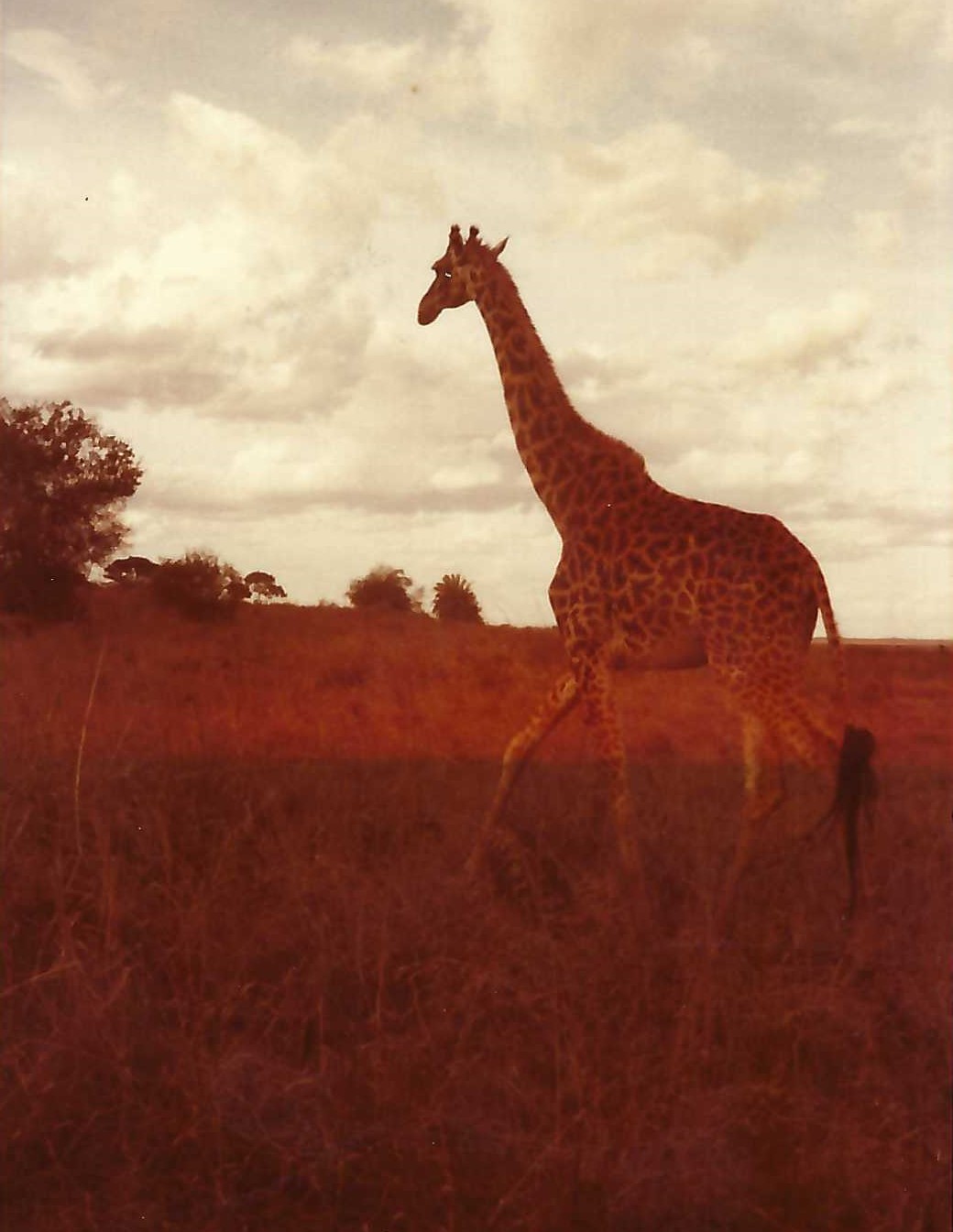

There, I lived in a small village in Botswana, Africa where I taught English as a second language, built a school library and coached the girls’ volleyball team. (I’ll admit, I also drank some beer and played some darts with the locals when work was done, football (soccer) on game weekends.) I also took advantage of opportunities to travel and all the adventures that entailed. I was immersed in a culture where the default was to accept strangers from distant lands as an opportunity to be valued for bringing a different perspective, customs and ways of knowing than what was their familiar experience.

During village leader meetings, the chief sat with villagers (and the likes of me) at the kgotla (a meeting compound), rich and poor, educated and non-, young and old, as equals to discuss life and the goings-on in the village. I earned a bit of special status in the village, being one of the few white people whom they’d ever encountered that could speak their language and assimilate into their culture and village livelihood. The group dynamics I learned in those gatherings naturally transferred to therapy dynamics and group work that I was to specialize in the future.

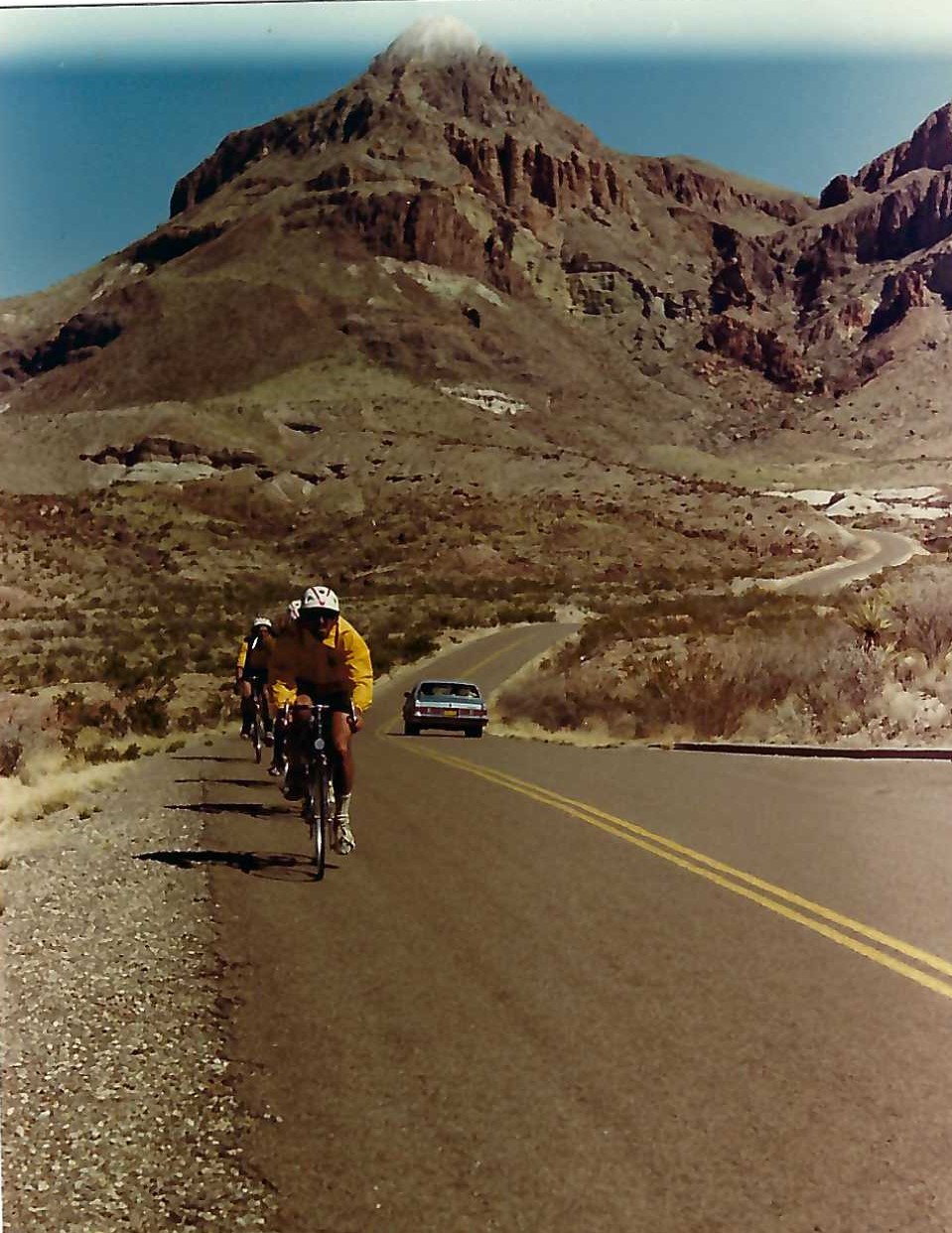

Returning to the U.S., somewhat discombobulated in the transition, I found VisionQuest and hired on as an English instructor for Cuban refugees who had been released from long-term, even life, prison sentences, later shipped to the U.S. (the Marietta boat lift), later enlisted in the program. My teaching role was soon to be cut short when a fluke vehicle accident left 2 of the trip’s staff counselors in the hospital. They had been training with the clientele for 2 months for the 2000-mile bike “quest” through the southwest ahead, and it was ready to leave in 2 days.

Panic was abound! A vision quest was not the kind of thing that you could just reschedule like a vacation after all the preparation and training and expectations that had been culled and built up for the embarkation of that life event. I hadn’t ridden a bike in many years, so of course I volunteered that I could be ready to bike across the country with no preparation. (Sound a little crazy? Well, it was. As I sometimes tell my clients, you have to be a little crazy to be any good at this therapy stuff.) I made a quick, crash course transition from teacher to camp counselor. I discovered (as did my supervisors) that I was good at it. The fire for becoming a counselor was kindled. Looking back, I now surmise that’s the first time I ever really knew what I wanted to do when I grew up. As an aside, I did survive the bike quest as well, from literally collapsing at the end of our first, 55-mile day to placing first among my Cuban comrades in the subsequent annual 100K Tucson bike race.

I later got promoted to program specialist, conducting intakes and preparation with hardcore juvenile delinquents (and their parents) for the arduous 1–2-year program ahead, strenuously geared to rehabilitate these incorrigible youths. They were mostly inner-city gang kids with multiple felonies who had exhausted all less extreme options for rehabilitation/detainment. The option that I starkly laid out was deal with us—the wilderness, wagon train, mules, and teepee living in camps—or youth prison. Not all of them were successful, but most were. Indeed, change was possible for even the most extreme of underdogs!

The psychologist that conducted the psychological evaluations requisite for program admission became a good friend of mine. One day he told me that I should pursue a graduate degree in counseling. I could only laugh at first…me, who had spent the past 7 years living about in the bush and the wilderness, having read barely more than a couple of books since my undergraduate years—really? Fast forward…in the end, I did. I may have been the only one who was surprised that I grew to flourish in the intellectual confines and clinical preparation of a prestigious doctoral program. After experiencing success with my first-ever bona fide psychotherapy client, I was hooked. I knew I’d found my niche. I was pleased to discover that I could meld my “in-the-trenches” experiences with higher academic learning. So, that I did -- graduating the top of my class while retaining my “country doc” ways.